Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has thrown greater challenges (as well as opportunities) for teachers and educators to deal with every day teaching-learning. Though, as a matter of policy guidelines as also the necessity, most went for emergency remote teaching through zooming/ googling, rather than pedagogically sound use of technologies and networks for teaching as well as student engagement in learning. This paper examines briefly the distinctive operation of distance and online learning (DOL), and the roles of DOL teachers and the competencies required of them to effectively function in the system and facilitate student learning. The roles and competencies have been scanned through and distilled from important, appropriate and contemporary published research studies and/or review analyses. At the end, distance and online teaching as reflective practice and as human activity has been underlined so as to sustain quality learning at the face of privatization and commercialization of (online) education and training. It is hoped that this piece may trigger some more reflections on the part of teachers and educators for more effective design of (blended) learning which the Covid- and post-Covid scenario will necessitate.

Distance and Online Learning: Role of Teachers/Instructors

When in past centuries teaching-learning went out of the classroom to more of non-formal education, open learning, self learning, and distance learning, many eyebrows were raised if this is possible, and if at all the teaching community has the competency to cope up with those new developments. The early distance education in forms of correspondence education and home study required the model of self-learning materials (based largely on programmed learning), postal communication, occasional teacher-students face-to-face interaction, and tutor comments on student assignments. The succession to distance education, due largely to the twin developments in research on pedagogies and applications in information and communications technologies (ICT), led to learning occurring in places different from teaching; educational organizations preparing self-learning materials (SLMs) and learner support services; using technological media (A/V, radio and TV, conferencing) to connect teacher-learner-content; two-way communication through SLM and learning centers for face-to-face counselling/dialogue; and teaching basically being directed to as individuals (Keegan, 2002; Holmberg, 1995). The onus of learning was on the learner, and the role of the distance teacher was that of tutor, counsellor, and facilitator.

Unlike single teacher who was responsible for F2F classroom teaching, distance teaching involved a ‘team’ (teaching at a distance), and the role of a ‘distance teacher’ involved: course design, development of SLMs (print, audio, video, multimedia), teaching through assignments and tutor comments, motivating students, monitoring student progress, conducting hands-on/practical, personal counselling, counselling at learning centres (may be by another colleague), evaluation of answer scripts (may be by another colleague). The teacher and content-centred paradigm shifted to learner-centred paradigm provided that the learning resources and teaching strategies have wider basket to choose from, so also the assignments and learning activities.

Online teaching/blended teaching extends the system of distance education through the semantic web and its possibilities of synchronous and asynchronous activities (same time-same place, same time-different place, different time-same place, different time-different place), and requires new sets of pedagogies and skills (Guasch et al, 2010; Salmon, 2004; Anderson et at, 2001).

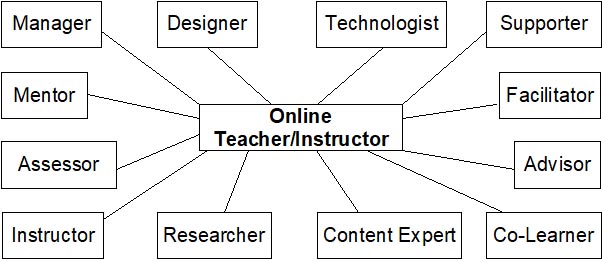

An online instructor today (like that of distance teacher) requires to play a plethora of roles (Yuksel, 2009) (Figure 1). One can check if one has played any or combination of these roles during Covid-19, and if all of these competencies can be acquired in due course so that post-Covid blended learning can be undertaken more effectively.

Figure 1: Portfolio of an online teacher/ instructor

What Lentell (2003) had underlined fifteen years ago still holds good today, though the context of DOL has changed considerably: that the distance teachers need to be knowledge experts, good communicators and listeners, designers, mentors and facilitators, and coordinators of resources. This, therefore, requires continuous research on perceived competencies and competency gaps by DOL teachers. In a recent study at UNISA, Roberts (2018) reported findings which are equally applicable to DOL teachers across the globe: that in the ranking of perceived roles and competency deficiencies, the teachers prioritized technology expert and instructional designer in that order, though mentoring and facilitating appeared at the bottom of the ranking. However, one has to be cautious since at times overconfidence and/or taken-for-granted competencies may not be flexible enough to undergo transformations through evolving times.

Competency Framework

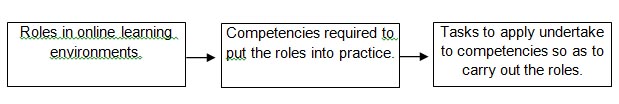

Based on the premise that online teaching-learning requires changes and adjustments in the organization of teaching and function of teaching, and that the teacher is a mentor and facilitator, Alvarez et al (2009) provided a role and competency framework for online teaching (Figure 2) which could be useful to review research on roles and competencies of online teachers.

Figure 2: Framework for roles and competencies of university teachers

Besides the ability to perform as per required standards, it also involves the ability to respond to and adjust with eventual requirements arising at the process of doing the tasks.

Review of Roles and Competencies of DOL Teacher

In what follows is an analysis of five reviews conducted in areas of teacher education, dephi study, validation of online teacher competencies, videoconferencing, and university teacher teaching-learning practices.

In the context of online teacher education, a comprehensive list of eight roles was developed by Bawane and Spector (2009) by juxtaposing reviews of competencies as well as roles underlined by various researchers (Table 1).

Table 1: Roles and competencies of online teacher educators

| Professional: ethical and legal standards, knowledge refreshing, commitment. Pedagogic: instructional strategy, learning resources, motivation, facilitate participation. Social: learning environment, conflict resolution, interactivity. | Evaluation: mentor, assessor, evaluator. Administrator: time management, rules and regulations. Technological: technological and learning resources. Counsellor: provide guidance. Researchers: conduct, interpret, integrate. |

The pedagogic role was identified as the most important of all, and included broadly the following:

- Design of instructional strategies: learning needs, learning outcomes, learning sequence, e-tivities.

- Development of learning resources: identify, select and develop resources, develop learning activities.

- Implementation of instructional strategies: integration of resources and activities, demo of effective presentation skills.

- Facilitation of participation: encourage, promote social interaction, facilitate collaboration.

- Sustenance of motivation: self-direction, effective feedback.

Using Delphi technique, Williams (2003) analysed role-specific competencies through strictly selected 15 experts and by cross examining through four rounds of consultations in the context of distance education (Table 2).

Table 2: Role-specific competencies distance education

| Roles | Competencies |

| Administration | Budgeting, marketing, strategic planning. |

| Instruction/Facilitation | Content knowledge, teaching strategies, internet skills, interaction and collaboration. |

| Instructional Design | Design of interactive technologies, media attributes, textual layout, internet tools, teaching strategies, learning styles. |

| Training | Advising and counselling |

| Technology Expertise | Technology operation, internet tools for instruction. |

| Graphic Design | Text layout, media attributes, internet tools. |

| Support | Advising, counselling. |

| Library | Research skills. |

| Evaluation | Education theory, competencies. |

In a validation of competencies for distance teaching, Darabi et al (2006) presented 20 skills (Table 3).

Table 3: Skills validated through review of literature

| 1. | Manage logistical aspects of the course |

| 2. | Exhibit effective written, verbal, and visual communication skills |

| 3. | Provide learners with course-level guidelines |

| 4. | Evaluate effectiveness of course |

| 5. | Assess learners’ learning based on stated learning goals and objectives |

| 6. | Create a friendly and open environment |

| 7. | Facilitate productive discussions |

| 8. | Stimulate learners’ critical thinking |

| 9. | Employ appropriate types of interaction |

| 10. | Provide timely and informative feedback |

| 11 | Identify when and how to use various instructional methods |

| 12. | Monitor learner progress |

| 13. | Employ appropriate presentation strategies to ensure learning |

| 14. | Ensure appropriate communication behavior within the given environment |

| 15. | Assist learner in becoming acclimated to the given environment |

| 16. | Encourage learners to become self-directed and disciplined in their educational pursuits |

| 17. | Foster a learning community |

| 18. | Use relevant technology effectively |

| 19. | Accommodate problems with technology |

| 20. | Improve professional knowledge, skills and abilities |

In the context of videoconferencing, skills relating to pedagogy, management, social, and technical were identified by Rehn et al (2018 (Table 4).

Table 4: Roles and competencies for videoconferencing

| Roles | Competencies |

| Pedagogic. | Teaching and communicating on screen; task and activity design, construction and negotiation of meaning, questioning, monitoring progress. |

| Management. | Planning, managing distributed locations, exchange of learning resources. |

| Social. | Facilitation of interaction, community of learners, building relationships and dealing with emotions, social presence. |

| Technical. | New technologies, operation, troubleshooting, student training, technology and discipline study. |

Since DOL today is viewed from the viewpoint of social learning and situated cognition, competencies as socially determined/dictated ‘task-adjustment’ is essential to visualize online teacher competencies (i.e. the role of the DOL teacher is not static and linear, and also that the competencies are not just given there). They are based on the requirements in-context and evolving social spaces of learning.

It has been pointed out that generally university teachers carry forward their notion of classroom teaching and traditional approaches to pedagogies to the context of DOL which does not work well (Kreber & Kanuka, 2006). Sometimes, this direct transfer creates tension in the traditional system getting into technology-enabled learning (TEL) (Natriello, 2005).

Beyond Competency: DOL Teacher as Reflective Practitioner

The role of critical reflection is crucial in the contexts of both institutional and faculty tension, as also quality of student learning. In a review of research carried out on studies conducted for two decades (1991-2011), Baran et al (2011) analysed three emergent issues in online teaching/teacher: empowerment, critical reflection, and technology-pedagogy integration.

It has been observed that the empowerment of DOL teachers should go beyond the functionalist approach (i.e. teaching as transmission of knowledge and values) to include competency and value ‘development’ through interaction, as also co-creation of content by both teachers and learners. Autonomy and critical reflection could contribute to self-direction and transformative learning. Teacher critical reflection on their own assumptions (their voice) on roles and competencies as also their actions should be built into such programme design.

It was Donald Schon (1988) who in the earlier work underlined the role of a reflective practitioner, and further articulated on ‘reflection in action’ and ‘reflection on action’ (after the activity). This brings up, across the board, any uncertainty, constraint, and conflict of values among teachers (and teaching organization) and between teachers and learners. This is important in the context of DOL teachers who deal with complex social information networks, and where the context changes due to constant shifting of spaces of information (content, activities, applications, cases, etc.). Such critical reflection may bring in more participatory pedagogical approaches and problem/inquiry based learning. Critical reflection by teachers is also essential to further promote critical reflection in learners.

Further, the assumptions about one’s own roles and actions are directly related to such assumptions about technology, and the relationship between technology and pedagogy. One such formulation/framework is technological-pedagogical-content-knowledge (TPACK) by Koehler et al (2007) and Mishra and Koehler (2006).

The most crucial pre-requisite for a teacher in a technology-enabled environment is understanding of and skills required for both technological and pedagogical applications for learning in diversified domain and conceptual contexts and flexible learning situations. It has been generally observed that those who possess one lack the other; and that only a few do appreciate the nuances of both. This becomes all the more difficult in the context of online and blended learning.

Technological affordances and teaching tasks (in specific contexts) are inextricably related to each other. Therefore, discipline pedagogy is essential for any intervention of professional development. My experience as a distance teacher is that expertise in common curriculum and instructional design works to an extent; beyond that we need specialists in discipline pedagogy, and that each discipline teacher can become an expert in discipline pedagogy as such.

Such professional development activities need to focus more on discipline-specific student learning, and discipline-specific applications of learning design and teaching-learning strategies. The large majority of distance teachers and teacher educators spend time and money to acquire expertise in online technologies, with little attention given to the relationship between content-technology-pedagogy inquiry. This is an area which needs significant attention and consideration. We need a framework in which online teachers are empowered, critical reflection and reflective practices are promoted, and technology is integrated into pedagogic inquiry.

In Conclusion

Along all that has been discussed above, the most crucial and the most under-weighed characteristic of a DOL teacher is that of commitment and conviction to constantly engage with learners as human beings, from a human point of view, beyond professional ethics – as constant mentor, facilitator, co-walker, co-contributor. We need to go beyond the economic and commercial models of distance education and training (Bramble & Panda, 2008) to ‘service’ and ‘happiness’ stances in learners as human beings and their learning development and social context.

References

Anderson, T.; Rourke, L.; Garrison, D. & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 5(5), 1-17.

Baran, E.; Correia, A.; & Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: critical analysis of the literature on the roles and competencies of online teachers. Distance Education, 32(3), 421-439.

Bawane, J. & Spector, M. (2009). Prioritisation of online instructor roles: implications for competency-based teacher education programmes. Distance Education, 30(3), 383-397.

Bramble, W.J. & Panda, S. (eds.) (2008). Economics of Distance and Online Learning. New York: Routledge.

Darabi, A.A.; Sikorski, E.G. & Harvey, R.B. (2006). Validated competencies for distance teaching. Distance Education, 27(1), 105-122.

Guasch,T.; Alvarez, I. & Epasa, A. (2010). University teacher competencies in a virtual teaching/learning environment: Analysis of a teacher training experience. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(2), 199-206.

Holmberg, B. (1995). The Sphere of Distance Education Theory Revisited. Hegan: ZIFF-FU.

Keegan, D. (2002). The Future of Learning: from e-Learning to m-Learning. Hegan: ZIFF-FU.

Koehler, M.J.; Mishra, P & Yahya, K. (2007). Tracing the development of teacher knowledge in a design seminar: integrating content, pedagogy and technology. Computers and Education, 49(3), 740-762.

Kreber, C. & Kanuka, H. (2006). The scholarship of teaching and learning and the online classroom. Canadian Journal of University Continuing Education, 32(2), 109-131.

Lentell, H. (2003). The importance of the tutor in open and distance learning. In A. Tait & R. Mills (eds.), Rethinking Learner Support in Distance Education. London: Routledge.

Mishra, P. & Koehler, K.J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: a framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017-1054.

Natriello, G. (2005). Modest changes, revolutionary possibilities: Distance learning and the future of education. Teachers College Record, 107(8), 1885-1904.

Roberts, J. (2018). Future and changing roles of staff in distance education: a study to identify training and professional development needs. Distance Education, Jan, 1-17.

Rehn, N.: Maor, D. & McConney, A. (2018). The specific skills required of teachers who deliver K-12 distance education courses by synchronous videoconference: implications for training and professional development. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 27(4), 417-429.

Salmon, G. (2004). E-moderating: The Key to Teaching and Learning Online. London: Routlege Falmer.

Schon, D. (1988). Educating the Reflective Practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Willams, P.E. (2003). Roles and competencies for distance education programmes in higher education institutions. American Journal of Distance Education, 17(1), 45-57.

Yuksel, I. (2009). Instructor competencies for online courses. Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences, 1, 1726-1729.

Professor Santosh Panda

Indira Gandhi National Open University,

New Delhi